Teacher's guide

Before you begin ...

Before you begin using the GUARDNA Teacher’s Guide, here are a few tips:

- In the PDF version of this guide, words highlighted in blue are explained in the Glossary section at the end of this document. On the website, these words are underlined with curved lines. By clicking on them you will get their definition in the GUARDNA context.

- Words or sentences underlined include a link to a website.

We would love to hear your opinion on the GUARDNA materials and the Teacher’s Guide: were the materials useful in supporting your teaching? Which improvements would you suggest? Did we missed anything out, what else would you like to see included in the materials? We would appreciate if you could email us your and your students’ questions or comments at education@nammco.org. We excitedly await your feedback!

Contents

1. Introduction

A thriving North Atlantic is crucial for the Nordic region, providing oxygen, food, resources, and climate stability. However, in recent decades human activities and climate change are threatening our oceans in general and some marine mammal species more particularly. In this context, GUARDNA-Guardians of the North Atlantic aims to educate the Nordic youth (ages 7–20) about the necessity of ocean conservation and help empower them as “blue allies” in the sustainable use of the marine environment. For this purpose, as marine mammals hold great significance for many people, GUARDNA uses them as iconic ambassadors of the ocean.

Educational materials focusing on marine mammals, the threats they face, how they are used, and users’ roles and responsibilities have been created. They include information cards, hands-on activities, and opportunities to get closer to real-world research. The goal is to engage students and raise awareness about the challenges that the broader marine ecosystem undergoes, understand the complexity and multitude of interactions, as well as the different circumstances and, therefore, the different approaches needed throughout the North Atlantic region.

NAMMCO (the North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission) is an intergovernmental organisation charged with ensuring the sustainable use and conservation of marine mammals in the North Atlantic. The GUARDNA project is spearheaded by NAMMCO with partners from the NAMMCO member countries and Denmark. As such, country-specific information is only given for the four NAMMCO countries (Faroe Islands, Greenland, Iceland, Norway) and Denmark.

1.1. About this guide

2. Activity Cards

2.1. Purpose

The Activity Cards present a wide range of exercises and hands-on activities, both indoors and outdoors. They are meant to be used in combination with the Information Cards, which provide complementary content and a wider context. These activities are designed to be adaptable across various subjects within the school curriculum, such as natural sciences, mathematics, language lessons, and ethics.

In this table, you will find the learning outcomes, i.e., the competence, your students will acquire through each activity. These outcomes are also listed on each activity’s page. They are country-specific and aligned with the national curriculum.

Some of the activities are to be performed outdoors to stimulate the exploration and conservation of local marine ecosystems. By actively engaging the students in their own coastal environments (e.g., learn about the local species and how they interact with one another), they encourage initiatives to promote environmentally responsible practices in their own communities, either coastal or inland. These activities will promote experimental learning and interdisciplinary connections, making ocean conservation relevant in multiple educational contexts.

Activities related to MINTAG and NASS24 allow students to follow real-world high-profile research, fostering a strong connection to the study of the ocean and increasing the engagement in STEAM education.

Note: Activities are continuously being added to the website, so check regularly for new content.

2.2. How to use Activity Cards

Below is a step-by-step guide on how we recommend using the Activity Cards.

- We recommend reading through the Teacher’s guide first to understand how the materials are conceived.

- Go to the website and open the desired activity under the Activities Once you are familiar with the materials, you can decide which activities are best suited for your students.

- The information to perform the activities can be accessed online or printed for use offline.

- Teachers can access the activity guide by clicking the “Download activity (Teachers)” button. This version includes answers and clarifications that are not available in the student version or on the activity’s main page, thus providing a thorough overview of the activity.

- The document available under “Download activity (Students)” contains the same information as shown on the website, namely, the instructions the students are meant to follow (with guidance from the teacher). It will likely be easier for the students to follow along if these are printed.

- All necessary materials are listed in the “Materials” section, including the handouts needed to complete the activity. We recommend distributing these to the students in printed form.

- The Information Cards that provide the background information to complete the activity are listed under the “GUARDNA Cards” section.

3. Information cards

3.1. Purpose

These cards deliver concise, age-adapted and accessible information about key aspects of ocean conservation and, in particular, marine mammals. GUARDNA is centred around several sets of Information Cards related to marine mammal species, threats, stakeholders, and uses. They are meant to enhance the students’ knowledge and understanding of marine ecosystems, as well as users’ needs and responsibilities.

A key element for several types of Information Cards is that they provide citable sources, which both teachers and students can look up for further information. Numbers inside square brackets indicate the information source. On the website, the reference list can be found at the end of each page. If you have downloaded a card, its reference list can be found under its corresponding topic section at the end of this Teacher’s guide, both on the website and in the PDF version.

QR codes at the bottom of a card lead to relevant pages on the NAMMCO website where more details and bibliography about that topic can be found.

3.2. Species Cards

Species Cards present information on marine mammals (cetaceans and pinnipeds) in the GUARDNA area. This includes facts, gathered by NAMMCO (check the website for further details), on the biology and ecology of each species, as well as their most updated abundance estimates in the most relevant area.

Some details to better understand the cards:

- The cards always include the species’ English name, scientific name, and common name in the six GUARDNA languages: Danish, Faroese, Greenlandic, Icelandic, Norwegian, and Northern Sámi.

- Adult length, weight, and maximum age: maximum known length, weight, and age the species can reach, regardless of sex. Often, males and females differ considerably in size and lifespan, and this differs from species to species (e.g., female blue whales are larger than males, male sperm whales are much larger than females, male killer whales are larger than females, but females killer whales generally live much longer).

- The Species Cards display the European IUCN conservation status, and indicates the date of that assessment, as the status may evolve with years. The IUCN status can be checked in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Sometimes, the global and European IUCN status are not the same, as the status of populations varies throughout their distribution range. For example, for some species, the global population may be Least Concern, while the European populations is Vulnerable or Endangered or vice-versa (e.g., the fin whale is Vulnerable at the global level but Least Concern at the European level). In parentheses we have included the year for that specific assessment.

- Geographical names (e.g., NA, NEA, Subarctic, Arctic) are shown in a map at the end of this page (see section Geographical terms) for clarification.

- Abundance estimates: it is impossible to count exactly how many marine mammals are in a given population, therefore their abundance is estimated through surveys and followed by (sometimes complicated) calculations. Because there is a degree of uncertainty involved in these estimates, they are typically reported with that uncertainty or as a range of possible values. For simplicity’s sake, the Species Cards show rounded “best” estimates. For some species, due to the logistical difficulty in surveying, there are no precise abundance estimates for some regions, and an approximate abundance estimate is given for a larger scale, sometimes global (e.g., Arctic or North Atlantic), but always including the hunting areas. For example, for harp seals and hooded seals, the abundance is given for the entire North Atlantic, as they are also hunted in West Greenland. The area the abundance estimate applies to is indicated on the card.

- The number of hunted animals is given as the average for 2019–2023 for the entire country. There might be several management areas within the same country. For the NAMMCO member countries, the yearly numbers taken in each management area can be found in the Catch Database.

- The number of hunted animals encompasses animal killed as food resource as well as those killed as protection against damage to fisheries and aquaculture. It does not encompass the number of by-caught animals, neither any animals illegally taken.

3.3. Stakeholder Cards

- the amount of influence they have during the decision-making process and

- how much their own life is directly affected by the topic and, therefore, their level of personal interest in decision-making.

3.4. Uses Cards

Since pre-historic times, stranded or hunted marine mammals have represented resources for many coastal communities worldwide, both in terms of food and materials but also as artistic and spiritual inspiration. More recently, their use for recreational purposes (seal and whale watching) has developed. The Uses Cards describe the multiple facets of the marine mammal resource.

3.5. Threat Cards

The sustainability of a population or species is a balance between its abundance, population dynamics (e.g., how quickly the species reproduces), and the level of direct (e.g., hunting, by-catch) and indirect (e.g., climate change) human impacts. It is important to note that a threat to an individual does not necessarily translate to a threat to the entire population; for instance, while hunting obviously endangers individual animals, responsible and sustainable hunting practices do not pose a threat to the population as a whole.

The Threat Cards give an overview of the threats or challenges that marine mammals face in the North Atlantic and whether we can easily mitigate them.

The coloured bar on the side of the first page indicates the ease or difficulty in quantifying and mitigating each threat, with red indicating a high degree of difficulty and green representing a lower degree of difficulty.

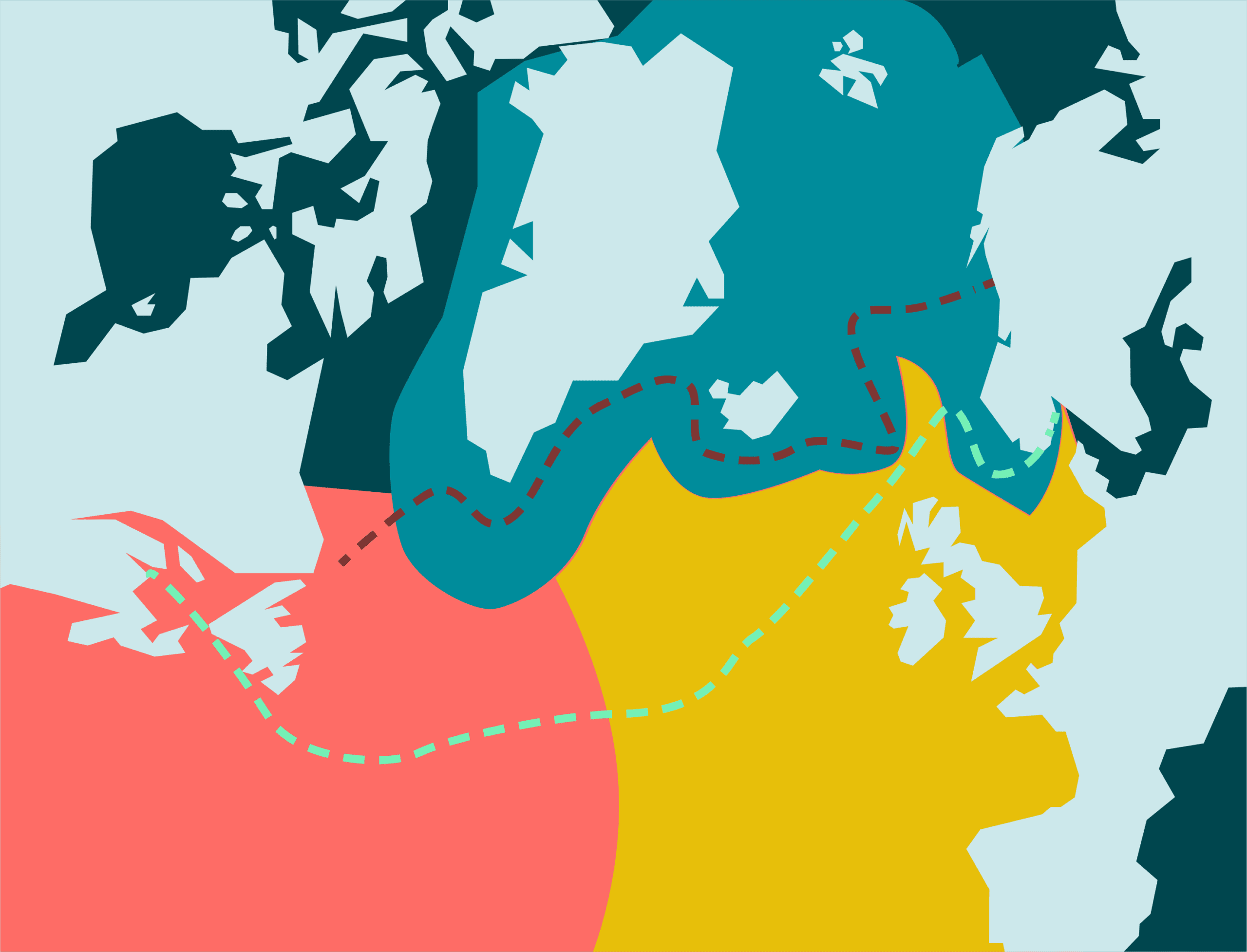

4. Geographical terms

- NAMMCO area: This encompasses the marine area surrounding the NAMMCO member countries (Faroe Islands, Greenland, Iceland, and Norway), both their Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) and the high seas.

- GUARDNA area: It encompasses the above areas plus the waters around Denmark.

- Arctic: The delineation of the Arctic region is taken as the boundaries established by the Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF).

- Subarctic: The region immediately south of the Arctic and north of the temperate regions in the North Atlantic.

- North Atlantic (NA): The northern portion of the Atlantic Ocean, extending from the equator northward towards the Arctic Ocean.

- North East Atlantic (NEA): Refers to the eastern portion of the North Atlantic.

area

area

area

area

area

area

5. References

Threats

By-catch and entanglement:

[1] Read, A.J., Drinker, P., & Northridge, S. (2006). Bycatch of Marine Mammals in U.S. and Global Fisheries. Conservation Biology, 20: 163-169. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00338.x

[2] International Whaling Commission. Conservation and Management – Entanglement of large whales. https://iwc.int/management-and-conservation/entanglement

[3] ASCOBANS. (2020, September 4). Bycatch – Still a Major Cause of Small Cetacean Mortality. https://www.ascobans.org/en/news/bycatch-%E2%80%93-still-major-cause-small-cetacean-mortality

[4] NAMMCO. By-catch, entanglement and ship strike. https://nammco.no/by-catch-entanglement-and-ship-strike

Climate change:

[1] Rantanen, M., Karpechko, A. Yu., Lipponen, A., Nordling, K., Hyvärinen, O., Ruosteenoja, K., Vihma, T., & Laaksonen, A. (2022). The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the globe since 1979. Communications Earth & Environment, 3(1), 168. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00498-3

[2] Kovacs, K. M., Lydersen, C., Overland, J. E., & Moore, S. E. (2011). Impacts of changing sea-ice conditions on Arctic marine mammals. Marine Biodiversity, 41(1), 181–194. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12526-010-0061-0

[3] Duengen, D., Burkhardt, E., & El-Gabbas, A. (2022). Fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus) distribution modeling on their Nordic and Barents Seas feeding grounds. Marine Mammal Science, 38(4), 1583–1608. https://doi.org/10.1111/mms.12943

Habitat degradation

[1] World Economic Forum. (2018, August 3). Only 13% of the world’s oceans are untouched by humans. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2018/08/new-map-shows-that-only-13-of-the-oceans-are-still-truly-wild/

[2] Marine Conservation Institute. 30×30: Protecting at least 30% of the ocean by 2030. Retrieved May 20, 2025, from: https://marine-conservation.org/30×30/

[3] OSPAR Commission. (2022, October 5). 11% of the North-East Atlantic is now protected. https://www.ospar.org/news/mpareport

[4] Akandil, C., Plekhanova, E., Rietze, N., Oehri, J., Román, M. O., Wang, Z., Radeloff, V. C., & Schaepman-Strub, G. (2024). Artificial light at night reveals hotspots and rapid development of industrial activity in the Arctic. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 121(44), e2322269121. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2322269121

Hunting

[1]

[2] Rocha, R. C., Clapham, P. J., & Ivashchenko, Y. V. (2014). Emptying the oceans: a summary of industrial whaling catches in the 20th century. Marine Fisheries Review, 76(4), 37-48. https://doi.org/10.7755/MFR.76.4.3

Noise disturbance

[1] Huntington, H. P., Boyle, M., Flowers, G. E., Weatherly, J. W., Hamilton, L. C., Hinzman, L., Gerlach, C., Zulueta, R., Nicolson, C., Overpeck, J. (2007). The influence of human activity in the Arctic on climate and climate impacts. Climatic change 82, 77–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-006-9162-y

[2] Tervo, O. M., Blackwell, S. B., Garde, E., Hansen, R. G., Samson, A. L., Conrad, A. S., Heide-Jørgensen, M. P. (2023). Stuck in a corner: Anthropogenic noise threatens narwhals in their once pristine Arctic habitat. Science Advances 9, eade0440. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.ade0440

[3] Jepson, P., Arbelo, M., Deaville, R. et al. Gas-bubble lesions in stranded cetaceans. Nature 425, 575–576 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/425575a

Pollution

[1] Jambeck, J. R., Geyer, R., Wilcox, C., Siegler, T. R., Perryman, M., Andrady, A., Narayan, R., & Law, K. L. (2015). Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science, 347(6223), 768–771. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1260352

[2] Kosior, E., & Crescenzi, I. (2020). Solutions to the plastic waste problem on land and in the oceans. In: T. M. Letcher (Ed.), Plastic waste and recycling (pp. 415–446). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-817880-5.00016-5

[3] James, N. A., & Große, A. (2023). Marine Mammals and Interactions with Debris in the Northeastern Atlantic Region: Synthesis and Recommendations for Monitoring and Research. In: Grimstad, S.M.F., Ottosen, L.M., James, N.A. (Eds.), Marine Plastics: Innovative Solutions to Tackling Waste. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-31058-4_1

[4] Jepson, P. D., & Law, R. J. (2016). Persistent pollutants, persistent threats. Science, 352(6292), 1388–1389. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf9075

[5] Borrell, A. (1993). PCB and DDT in blubber of cetaceans from the northeastern north Atlantic. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 26(3), 146–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/0025-326x(93)90125-4

[6] International Whaling Commission (IWC). (2020). Report of the IWC Workshop on Marine Debris: The Way Forward, 3-5 December 2019, La Garriga, Catalonia, Spain. SC/68B/REP/03. Available at https://archive.iwc.int/pages/view.php?ref=17025&k=

[7] Nelms, S. E., Barnett, J., Brownlow, A. et al. (2019). Microplastics in marine mammals stranded around the British coast: ubiquitous but transitory? Scientific Reports, 9, 1075. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-37428-3

[8] Jepson, P. D., Deaville, R., Barber, J. L. et al. (2016). PCB pollution continues to impact populations of orcas and other dolphins in European waters. Scientific Reports, 6, 18573. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep18573p

[9] Murphy, S., Barber, J. L., Learmonth J. A. et al. (2015). Reproductive Failure in UK Harbour Porpoises Phocoena phocoena: Legacy of Pollutant Exposure? PLoS ONE, 10(7), e0131085. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0131085

Ship strike

[1] Tournadre, J. (2014), Anthropogenic pressure on the open ocean: The growth of ship traffic revealed by altimeter data analysis. Geophysical Research Letters, 41, 7924–7932, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014GL061786.

[2] Leaper, R. (2019). The role of slower vessel speeds in reducing greenhouse gas emissions, underwater noise and collision risk to whales. Fontiers in Marine Science, 6, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2019.00505

[3] DFO (2014). Science review of the final environmental impact statement addendum for the early revenue phase of Baffinland’s Mary River Project [Science Response 2013/024]. DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2014/mpo-dfo/Fs70-7-2013-24-eng.pdf

[4] Laist, D.W., Knowlton, A.R., Mead, J.G., Collet, A.S. and Podesta, M. (2001). Collissions between ships and whales. Marine Mammal Science, 17, 35-75. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.2001.tb00980.x

[5] Ifaw (2021). Ship strikes and whales: preventing a collission course. https://d1jyxxz9imt9yb.cloudfront.net/resource/1114/attachment/original/Ship_strikes_and_whales_-_factsheet.pdf

[6] Marine Mammal Commission (n.a.). North Atlantic Right Whale. https://www.mmc.gov/priority-topics/species-of-concern/north-atlantic-right-whale/

Tourism

[1] Arctic Portal. (n.d.). Sustainable Arctic Tourism. https://arcticportal.org/shipping-portlet/tourism

[2] Bejder, L., Higham, J. E., & Lusseau, D. (2022). Tourism and research impacts on marine mammals: A bold future informed by research and technology. In Marine Mammals: the Evolving Human Factor (pp. 255-275). Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-98100-6_8

[3] Bearzi, M. (2017). Impacts of Marine Mammal Tourism. Ecotourism’s Promise and Peril, 73–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58331-0_6

Uses

Biomimicry

[1] Lebdioui, A. (2022). Nature-inspired innovation policy: Biomimicry as a pathway to leverage biodiversity for economic development. Ecological Economics, 202, 107585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2022.107585

[2] Baleen Filter (n.d.). https://www.baleenfilters.com/

[3] Biomimicry Institute [@biomimicryinstitute]. (2024, February 18). Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/biomimicryinstitute/p/C3fczQbPaAn/

[4] Goulet, P., Guinet, C., Swift, R., Madsen, P. T., & Johnson, M. (2019). A miniature biomimetic sonar and movement tag to study the biotic environment and predator-prey interactions in aquatic animals. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2019.04.007

Clothes and artefacts

Food

[1] Ziegler, F., Nilsson, K., Levermann, N., Dorph, M., Lyberth, B., Jessen, A.A., & Desportes, G. (2021). Local Seal or Imported Meat? Sustainability Evaluation of Food Choices in Greenland, Based on Life Cycle Assessment. Foods, 10(6):1194. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10061194

[2] Shahidi, F., & Synowiecki, J. (1996). Seal meat: A unique source of muscle food for health and nutrition. Food Reviews International, 12(3), 283–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/87559129609541082

[3] Geraci, J., & Smith, T. (1979). Vitamin C in the Diet of Inuit Hunters From Holman, N.W.T. Arctic, 32(2), 135-139. https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic2611

Recreation

[1] O’Connor, S., Campbell, R., Cortez, H., & Knowles, T. (2009). Whale Watching Worldwide: tourism numbers, expenditures and expanding economic benefits (Special report from the International Fund for Animal Welfare). Yarmouth, USA. https://www.cms.int/sites/default/files/document/BackgroundPaper_Aus_WhaleWatchingWorldwide_0.pdf

[2] Marine Mammal Commission (n.d.). The Value of Marine Mammals. https://www.mmc.gov/priority-topics/value-marine-mammals/

[3] Cottam, B. (2023). Gone wild: is wildlife tourism out of control?. Geographical. https://geographical.co.uk/wildlife/is-wildlife-tourism-out-of-control

[4] Jimenez, M. P., DeVille, N. V., Elliott, E. G., Schiff, J. E., Wilt, G. E., Hart, J. E., & James, P. (2021). Associations between nature exposure and health: a review of the evidence. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(9), 4790. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094790

[5] Vert, C. (2020). Health Benefits of Blue Spaces During a Pandemic. IS Global.https://www.isglobal.org/en/healthisglobal/-/custom-blog-portlet/espacios-azules-beneficios-para-la-salud-en-tiempos-de-pandemia/

Stakeholders

Consumers

[1] Robards, M. D., & Reeves, R. R. (2011). The global extent and character of marine mammal consumption by humans: 1970–2009. Biological Conservation, 144(12), 2770-2786. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2011.07.034

[2] Attitudes to Whaling: Norway 2019. A survey commissioned on behalf of: Animal Welfare Institute, Cetacean Society International, Humane Society International, NOAH: For Dyrs Rettigheter, OceanCare, Pro Wildlife, and WDC, Whale and Dolphin Conservation. https://uk.whales.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2019/10/norway-whaling-whalemeat-attitudes-survey-2019.pdf

[3] Egeland, G. M., Pacey, A., Cao, Z. & Sobol, I. (2010). Food Insecurity among Inuit preschoolers: Nunavut Inuit Child Health Survey, 2007-2008. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 182(3): 243-248. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.091297

[4] Food and Agriculture Organization. The right to food. https://www.fao.org/right-to-food/background/en/

[5] Young-Powell, A. (2022, March 28). ‘Meet us, don’t eat us’: Iceland turns from whale eaters to whale watchers. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/mar/28/meet-us-dont-eat-us-how-iceland-is-turning-tourists-from-whale-eaters-to-whale-watchers

[6] NAMMCO 2017. Marine Mammals: A multifaceted Resource. (Revised version from August 2021). https://nammco.no/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/marine-mammals-a-multifaceted-resource_rev0821.pdf

Whale and seal watchers

[1] O’Connor, S., Campbell, R., Cortez, H., & Knowles, T. (2009). Whale Watching Worldwide: tourism numbers, expenditures and expanding economic benefits (Special report from the International Fund for Animal Welfare). Yarmouth, USA. https://www.cms.int/sites/default/files/document/BackgroundPaper_Aus_WhaleWatchingWorldwide_0.pdf

[2] Koetje, J. (2020). Whale watching – A win-win for the economy and the whales in Massachusetts. National Marine Sanctuaries. https://sanctuaries.noaa.gov/news/dec20/whale-watching-in-stellwagen-bank.html#:~:text=A%20recent%20study%20revealed%20that,can%20be%20an%20unforgettable%20experience

[3] Suárez-Rojas, C., Hernández, M. M. G., & León, C. J. (2023). Sustainability in whale-watching: A literature review and future research directions based on regenerative tourism. Tourism Management Perspectives, 47, 101120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2023.101120

[4] Bejder, L., & Samuels, A. (2003). Evaluating the effects of nature-based tourism on cetaceans. In N. Gales, M. Hindell, & R. Kirkwood (Eds.), Marine mammals: Fisheries, tourism and management issues (pp. 229-256). CSIRO Publishing.

[5] Zeppel, H. (2008). Education and conservation benefits of marine wildlife tours: Developing free-choice learning experiences. The journal of environmental education, 39(3), 3-18. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOEE.39.3.3-18